In my author newsletter, you can find stories where I’ve had to mimic the styles of other writers. This includes the serials The Last Temptation of Winnie the Pooh and Kraken in a Coffee Cup, the latter of which is largely made up of shuffled passages from Moby Dick and tells the tale of a ship that sales beneath the seas, claiming the souls of drowned sailors. One key factor in making these projects work is mirroring the original author’s style, but that’s not the only reason such an exercise in style is useful. In studying their style, we learn to expand our own.

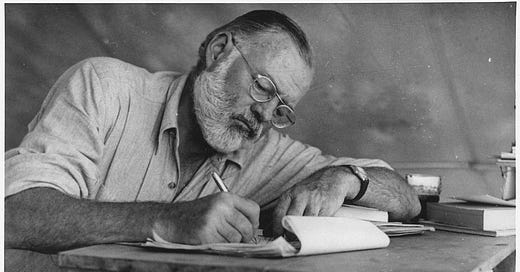

One of my earliest endeavors of this sort was the short story, The Sphinx and Ernest Hemingway, and Hemingway seems as good a place to start as any. As with every author, we pick and choose what we want to emulate. Hemingway is famous for his iceberg theory of writing, and there are many wonderful applications of this today. However, I don’t study Hemingway for what he hides, no matter how proud he was of this conceit.

I don’t, because, as a pioneer, his use of the method is crude and immature. That seems a brash statement, but this is the way of pioneers. He could write a story that seemed to be about nothing, but beneath the surface, it’s a Jerry Springer episode. That’s not what I hoping to capture.

As an aside, let’s talk about what I am hoping to capture as a writer. Once upon a time, fantastic stories had to use simple, straightforward language, and realistic stories could use fantastic language. This was expressed by Orson Scott Card in his book, Writing Science Fiction and Fantasy, where he talks about the metaphor of the serpentine bus. Literary readers understood this was a bus with according connections between its sections, giving it its signature movement. Readers of speculative fiction assumed it was public transportation involving dragons.

I want speculative fiction with the prose and form experiments usually reserved for realistic stories. That’s what I hope to achieve as a writer.

Let’s get back to our study and begin with Hemingway’s use of parataxis.

Parataxis is the placement of clauses or phrases one after another, without conjunctions to connect them. The causation is implied instead of stated, with each cause being its own little story.

Manuel drank his brandy. He felt sleepy himself. It was too hot to go out into the town. Besides there was nothing to do. He wanted to see Zurito. He would go to sleep while he waited.

“Men Without Women,” Ernest Hemingway

There is little to connect one idea to the next, other than the word, “besides.”

As I opened my own story, I could have aped this style much more than I did:

The sphinx laps at the river in a gully thick with the scent of two young male lions, evicted by a father now wary of the competition. Left alone, they will find another pride, separately or together, kill the elder male and his children, and claim the females for their own. The sphinx ponders this as she flicks her tail like a lioness in heat. She seeks no justification for what she means to do, nor is she motivated by compassion for the young who would be slaughtered. She loves the riddle of their behavior, and that is all.

“The Sphinx and Ernest Hemingway,” Thaddeus Thomas

I could have written, “The sphinx laps at the river in the gully. The air is thick with the scent of two young male lions…”

I didn’t, and I can’t tell you my reasoning other than I probably had never heard the word parataxis. I was writing Hemingway by ear, and while his use of the style results in text that is often short and clipped, there’s always more to it than that:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.

A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway

Each sentence is easy to follow and presents a clear image, and those images accumulate, adding to and interacting with one another, until the entire paragraph presents a complex image built of seemingly simple parts.

Let’s take another look at the last sentence in that example. It begins with three clauses in a compound structure (minus the usual punctuation), an echo of his usual abrupt phrases, but this time connected with conjunctions. Instead of ending, the sentence continues, using a cumulative syntax that is another signature of Hemingway and uses those -ing ending words that are so often labeled “off limits” by today’s writers.

“…and we saw…”

the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.

Note, too, how Hemingway confounds the modern expert who tells us that short, clippy sentences are for action. All the shorter sentences, Hemingway used to set the scene, but the action of the moment, that chaos of dust and leaves left in the wake of the marching soldiers, is captured in cumulative syntax which gives the action its movement.

Let’s take a look at the story “Cross Country Snow” from Hemingway’s collection, In Our Time. I’ll preface the quote by explaining that, in “the telemark position,” a skier makes a jump turn and crouches while trailing his ski poles.

George was coming down in the telemark position, kneeling, one leg forward and bent, the other trailing, his sticks hanging like some insect’s thin legs, kicking up puffs of snow, and finally the whole kneeling, trailing figure coming around in a beautiful right curve, crouching, the legs shot forward and back, the sticks accenting the curve like points of light, all in a wild cloud of snow.

It’s easy to forget this side of Hemingway when we describe him as simple syntax: noun, verb, predicate; noun, verb, predicate. His action compounds on itself, in this case beginning with a declarative phrase before the much-maligned -ing verbs build off that foundation, and build and build and build…all in a wild cloud of snow.

What do we take away from Hemingway’s example? We can learn from the syntactical styles he employs, certainly, but there’s something deeper for us here. He applied style intentionally, according to the impact he was trying to achieve, and having found his stylistic extremes, parataxis and compounding, he used them consistently, as if composing music rather than simply conveying ideas.

His use runs counter to what society often presumes of his writing and to the basic tenets of today’s writing instruction for new writers.

Two key points: clarity; communicating a story is difficult enough. Make your images and ideas as clear as possible. Style; you can apply your favorite techniques in a consistent manner that develops a style readers will associate with you, but remember that variation is key.

— Thaddeus Thomas

Are you an author with a book to promote or a newsletter that needs more subscribers? I’m offering managed Bookfunnel services. Visit Bookmotion.pro to see the books I’m working with now and to get more information.

This is wonderful, Thaddeus, rich in insight

Hey, I loved this. I had no idea Parataxis was a thing. I realize now that maybe I use it a little too much in my stories.

Keep these going, they’re great, man!